Your cart is currently empty!

29 Feb No Land Tattoo collaborates with artist Joan Torres to create the first Falla in history centred around tattoo iconography

By Marta Moreira.

The Fallas and contemporary art have been exchanging glances for decades. Graphic design, graffiti, or even conceptual art have gradually penetrated Valencia’s folkloric festivals, contributing to establishing a route for alternative or experimental Fallas that generate more interest each year, both within and independent to the realm of exclusively Falleros.

However, up to this point, the world of tattoos had only been tangentially present in The Fallas. Not one monument had ever centred its theme exclusively around the symbolic and aesthetic universe of this form of artistic expression. The Nicolau Andreu Commission from Torrente, a town located little more than ten kilometres from the city of Valencia, will be the first to do so thanks to the affiliation with fallero artist Joan Torres and No Land Tattoo Parlour.

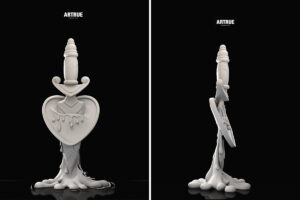

This coming 15th of March, an almost six metres high and three metres wide falla will be erected in Calle San Juan de Ribera 17 in Torrente, whose central figures refer to three iconic depictions of traditional tattoo imagery: a lighthouse, a heart pierced by a dagger, and a pin-up style mermaid with a snake coiled around her body. The latter will be presented at this year’s Ninot Indultat contest. [Ninot Indultat is a single figure from a falla sculpture which is “pardoned” and freed from the burning. It’s kept for exhibition as a trophy and for historical-archivist purposes. Only one out of all fallas is awarded this prize each year making it a great honour]. The strive for improvement, the empowerment of women, and humanity’s relationship with nature in regards to climate change are some of the current concepts with which the members of this commission have wanted to relate these universal symbols of old school tattoos.

To design this monument, Joan has collaborated with Sento Biosca, a veteran tattoo artist and owner of No Land Tattoo Parlour, a studio he was already acquainted with as a client and friend. His punk rock roots and his fondness for tattoos date back a long way, so dedicating a Falla to this world was very natural for him. “For this project, I wanted to collaborate with a renowned tattoo artist and studio, which is why I thought of No Land. I got excited because, except for a falla Ninot (ninot is a single falla figure) designed by fallero artist Sento Llobell for Falla Na Jordana a few years ago, this would be the first one dedicated entirely to tattoo symbology.”

“One of the things we were clear on from the beginning was that the iconography had to be very symbolic and recognizable to everyone, so that not only those who were familiar with the world of tattoos could understand it,” explains this Fallero artist who is known for creating unconventional Fallas with a distinct style drawing on flat lines and disproportion.

Despite not being actively involved in the Fallas and even understanding how complex it would be, Sento accepted the commission immediately. “To see your designs translated into sculptures has been beautiful, and it has been a very interesting process. Although I only did two-dimensional drawings, and someone else turned them into 3D drawings for modelling, the reality is that there are many things to consider when designing, which were all new to me. For example, seeing as the figures have to be supported on a stable base, you have to take into account that, internally, they usually have a pyramidal-shaped structure. Another important aspect to consider is that you can’t go beyond certain dimensions and some figures may need to be dissected to be transported in trucks for the Plantà (the installation or staging in the street). For instance, at first, I drew the mermaid in a foreshortened position, with one hand touching its tail, but then I had to change the position of the hand and add a belt to conceal the seam at her waist which would need to be made in order to transport the figure from the workshop to the street.”

A complex process

“This Falla has been difficult to build, I’m not going to lie,” confesses Joan. “Collaborating with a third-party designer is more difficult than doing it all by yourself. But it’s been worth it.”

According to him, there are several ways to fashion a Falla. Sometimes it’s done in real-time, starting from a flat board from which a silhouette is cut out, carved and assembled. But in this case, they worked from machine-milled figures produced from a 3D design. “We put them through CNC machines that create three-dimensional objects in cork and expanded polystyrene. From there, you carve, brush, and sand until the figure is perfectly modelled according to the original design.”

After modelling, the interior structure is built, which is usually made of wood. “Sento had to preplan the pin-up’s pose so that the base would be stable, because on paper, anything holds up, but in reality…” Even so, he explains, when translating the design into a 3D form, some adjustments had to be made to the original drawing for safety reasons and for smoother work. “Each time something was modified, I communicated it to Sento beforehand for his approval. He understood perfectly well that there were small adjustments that needed to be made for the Falla to be feasible.”

After the structure, it’s time to paper over the monument with thin cardboard and a homemade water and flour paste with the intention of hardening the piece. “Then, we give it three to four layers of stipple [a textured coating], and then we have to sand the piece to refine the forms as much as possible. Before starting to paint with a spray gun, I give it a coat of synthetic varnish to ensure that the stipple doesn’t come off.”

Another differentiating detail of this Falla is the use of markers to mimic the thick black line used in traditional tattoos to outline the contours of the silhouettes, as well as the tattoos directly painted by Sento on the pin-up’s body after completion of the sculpture. Once everything is ready, a hydrophobic spray is applied to repel water in case of rain and… voilà!

A Fallero artist who worked for Legoland and Marvel Dubai

Joan Torres’s principal mentor was Antonio Verdugo, from whom he learned the secrets of the trade after completing his Advanced Degree in Fallas Arts and Scenography. Another of his great points of reference was the renowned comic book artist Sento Llobell (Valencia, 1953), affiliated with the so-called New Valencian School. “He was the father of one of my best friends, so I spent a lot of time with him and paid close attention to his work because I’ve always been fond of the visual arts and drawing ever since I was a child.”

Joan not only perfected his talent for design, model making, and building structures in Falla workshops. In Romania, he worked creating figures and reproductions for theme parks such as Legoland and the Marvel park in Dubai. A few years later, in Portugal, he specialised in creating scenography for major events. “At that time, I crafted many artificial rocks and waterfalls,” he recalls.

Since setting up his own workshop in Sagunto in 2023, he has received commissions from renowned committees such as Cuba-Puerto Rico or Séneca-Yecla. “I’m fortunate that they always give me a lot of freedom because, in truth, they hire me because they are looking for something different,” he explains. “The Torrente Falla, in fact, has had a years.”

The first “modern” Fallero artists in history

The precursor of contemporary experimental Fallas was Ricardo Rubert (Burjassot,1923 – Granada,1991), a Fallero artist who decided in the early sixties to abandon the stylistic conventions of the Valencian Neo-Baroque to investigate more stylised and schematic forms of visual representation, and additionally, using new materials. His “Disintegrated Fallas,” in which he gave importance to the creation of voids in the monument’s interior and playing with light, space, and textures, have earned him the widely-known nickname “El Loco.”

In 1965, he retired from the Fallas festivities and began working as a set decorator on films such as “Doctor Zhivago,” “Nicholas and Alexandra,” and “El Sur,” as well as decorating nightclubs and cafes in Madrid and creating figures and ephemeral constructions for amusement parks.

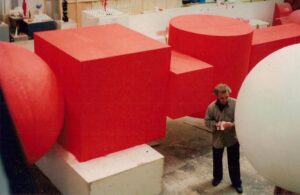

Alfredo Ruiz (Valencia, 1944) continued Rubert’s legacy into the seventies, transgressing conventions to create increasingly refined monuments, inspired by the Russian avant-garde of Malevich and Kandinsky and abstract minimalism. It was not only an aesthetic revolution but also thematic: he was also among the first to introduce themes of reflection into the Fallas such as environmentalism, inequality, capitalism, racism, or to question the death penalty.

This radical change in visual language has generated much controversy among the purist public, but at the same time, it has favoured the interest of many people outside the Falla’s world in these iconoclastic pieces. After Alfredo Ruiz, many other pioneers have come along, contributing to creating a kind of “alternative route” of unconventional Fallas in which often the Fallero artist collaborates with a contemporary creator from other fields, as is the case with Escif, Okuda, Reyes Pe, Giovanni Nardín, Julia Navarro, Miguel Hache, or Dídac Ballester. Although for some in the Fallero sector, it is still inconceivable that there could be horizontal, audiovisual or inflatable monuments, or created with textile materials. The truth is that the rejuvenation of distinct languages in the Fallas is irreversible.